In our continuing interview series with today’s top production designers, we interview Production Designer Ethan Tobman about his latest project, Room.

This year at the Toronto International Film Festival I fell in love with a film that absolutely broke my heart. I found myself weeping during and after the screening which I haven’t done in a very long time.

That film was Room.

Room follows a mother and her five year old son, Jack, who was born into captivity after Ma was kidnapped and sexually assaulted for years by her captor, leaving the two of them to live their lives in one small room- a shed in his backyard.

While all of this is very grim, the film takes the refreshing point of view of the curious and imaginative child who is still amazed by his small but wondrous world.

Upon Jack’s fifth birthday he is told about the outside world and they make a plan to escape. Jack is Ma’s only hope. However, once free, will anything ever be the same again?

Recently I interviewed Room’s production designer, Ethan Tobman, who had the unique task of designing a room, with director Lenny Abrahamson, so important to the telling of the story yet so small it would be nearly impossible to shoot. Rarely is production design this integral to the plot and characters of a story that I am so enthralled by its process. Here’s what he had to say.

Q&A with ‘Room’ Production Designer Ethan Tobman

ROSE: Hi Ethan! It’s so nice to be speaking with you.

ETHAN TOBMAN: I’m such a fan of your site. I’m thrilled to be speaking with you. I’ve been following your site for 5 years so it’s a real pleasure.

ROSE: Wow, I had no idea you’d been following for that long! That’s great. I saw Room at TIFF and I cried my eyes out. It’s my favourite movie this year thus far.

ETHAN TOBMAN: We felt an enormous responsibility to get this right so when people tell me they were moved by it in the way that we hoped they would be, I feel an enormous sense of relief more than anything.

ROSE: How did you get on board the project? Have you worked with Lenny before?

ETHAN TOBMAN: I designed the movie What If for producers David Gross, Jesse Shapira and Jeff Arkuss that shot in Toronto and was well received. The week Lenny and I met I had just designed the Ok Go video “The Writing’s On The Wall” where we pulled off some complex optical illusions and the video was going viral. Lenny loved it and I think we both appreciated what a brain-teaser Room would be. Our one hour meeting lasted 3 or 4, we talked about art, politics, religion, and a teeny bit about film.

ROSE: What was your design process like with Lenny? Were you allowed a lot of creative freedom to explore? Was Lenny right there with you?

ETHAN TOBMAN: Lenny is the greatest of rare directors that encourage- thrive on other people’s ideas while never sacrificing their own. Every frame of Room is Lenny’s film, it is precisely the film he set out to make, but he was so patient and encouraging of the creative voices within his war chest that myself, Danny Cohen, Nathan Nugent, Ed Guiney and the cast all felt like a tremendously close family by the time Room was over. Many of my initial sketches for ‘room’ and Nancy’s house are very similar to what made it on screen, but we would research and refine their details and backstory till we were certain they stayed true to Lenny’s vision and Emma’s story.

Director, Lenny Abrahamson on set during a rehearsal with Brie Larson and Jacob Tremblay

ROSE: Watching Room from an art department standpoint I remember thinking, wow, such a small but endlessly important room for a large amount of time and you have to fit the cameras and have space for actors and crew. It’s an interesting production design challenge.

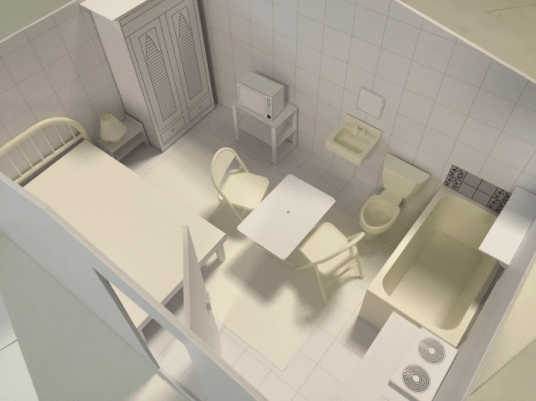

ETHAN TOBMAN: As a designer I’ve always felt, and we were taught this in design school, that without a box, you can’t think outside of something so, for example, if you’re giving a design student no restrictions, the designs tend to be a little less inspired and have less ingenuity than if you provide them with some restrictions they have to overcome. So I think all of us as a team and particularly myself as the designer had to approach the obstacles here by embracing them and using them to our advantage as storytellers. So, what are the obstacles? You have a minor. A child who can not work more than 8 hours a day and between his meals, his bathroom breaks and his education, you really have him for 5 hours a day. You have an incredible amount of dense drama to cover on the page and you have 70 film technicians who each need access to the space to hit very precise targets. So from the very beginning I approached this as an inverted Rubik’s Cube and the idea was that we build it entirely modularly so every panel and every square could be removed from the outside to allow us to peer in. Similarly we approached each environment within room as a world unto itself. So for example, the wardrobe is like a planet in a solar system kind of how Jack would see it but also how we would film it. We built multiple wardrobes where each side of the wardrobe was removable to allow for different camera angles and different filmic intimacy. So that’s how we approached it from the outset.

ROSE: You guys filmed this at Pinewood in Toronto, yes?

ETHAN TOBMAN: We filmed it at Pinewood on a sound stage. The first half of the film was on a soundstage, and we were racing to finish ahead of schedule to allow more time for the actor’s to rehearse and familiarize themselves within ‘room’. Once we left ‘room’ our next challenge was being in different locations every few days, and erasing snow off the ground when we were attempting to capture fall.

I think one of the other greatest restrictions where I worked more in tandem with our phenomenal DOP Danny Cohen than any cinematographer I’ve ever worked with was the restriction of one source of sunlight and 2 practicals for 45 minutes of filming. So I did extensive rendering and animation research on 3D Studio Max where we prodded light facing north, east, south and west. We experimented with different GPS locations in Ohio where the house would have been and that taught us how the sun trajectory would look throughout the day at this time of year and it also taught us where the walls would be bleached, where they’d be overexposed to sun, which parts of the room never were exposed to sunlight and that became an incredibly rich template for how to manage the palette within the cork walls of room which tell so much history and give details to so much life.

ROSE: What was your most satisfying moment on the film? On the other side of that- what was your biggest challenge?

ETHAN TOBMAN: After 6 weeks of building ‘room’ and with 2 days left before shooting, I spent the weekend inside ‘room’. I actually slept there one night. I felt we had missed something, as we often do before Day 1. I decided Ma would have wanted to document Jack’s childhood. Without a camera, I felt she would have drawn pictures of him on any paper or grocery bag Old Nick might have discarded. I got photos of Jacob as a child and drew some and made a tree collage out of them and pinned them to a wall. On such a small set, this took up an enormous amount of real-estate, but Lenny and Danny and Brie loved it when they walked in and it ended up being that missing thing that you can’t put your finger on.

My biggest challenge with Room was designing it’s exterior. I wanted it to feel startlingly innocuous: The only extraordinary thing about Room’s exterior is how un-extraordinary it is. I dreamt a lot about that shed before presenting the least cinematic exterior research could muster. At first, the cast and crew were shocked by it. And it was precisely the reaction I had hoped for. At the time it seemed a bold choice not to age or personalize it in any way- no wear and tear, hardly any distressing. But then, how so much life could exist inside something so insignificant was precisely what drew me to the story.

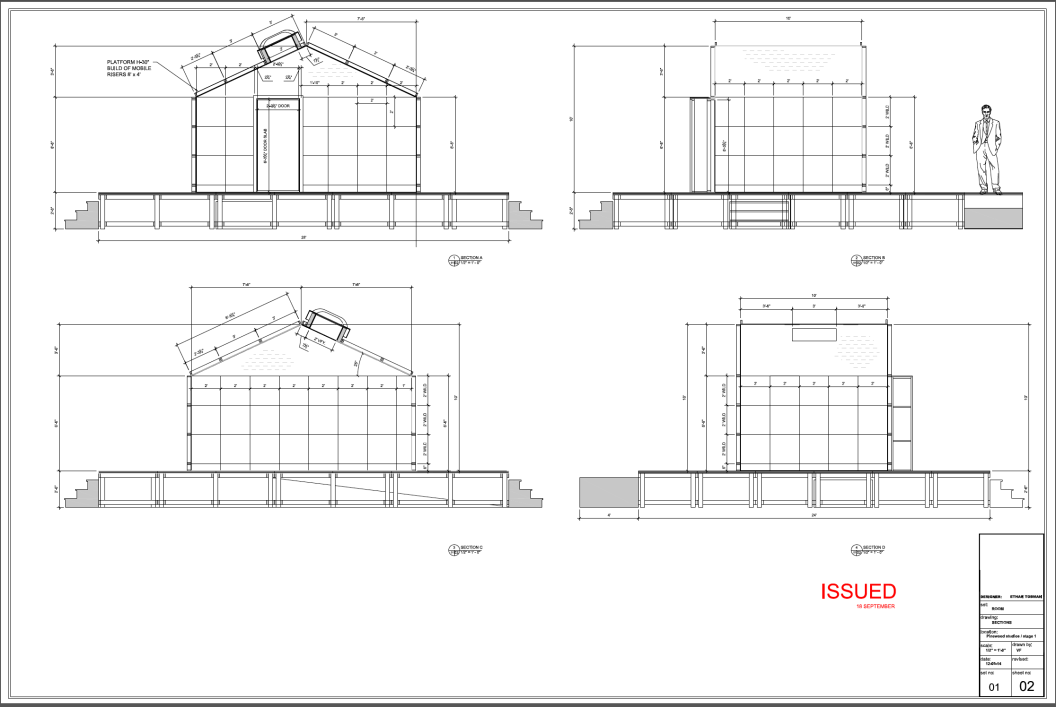

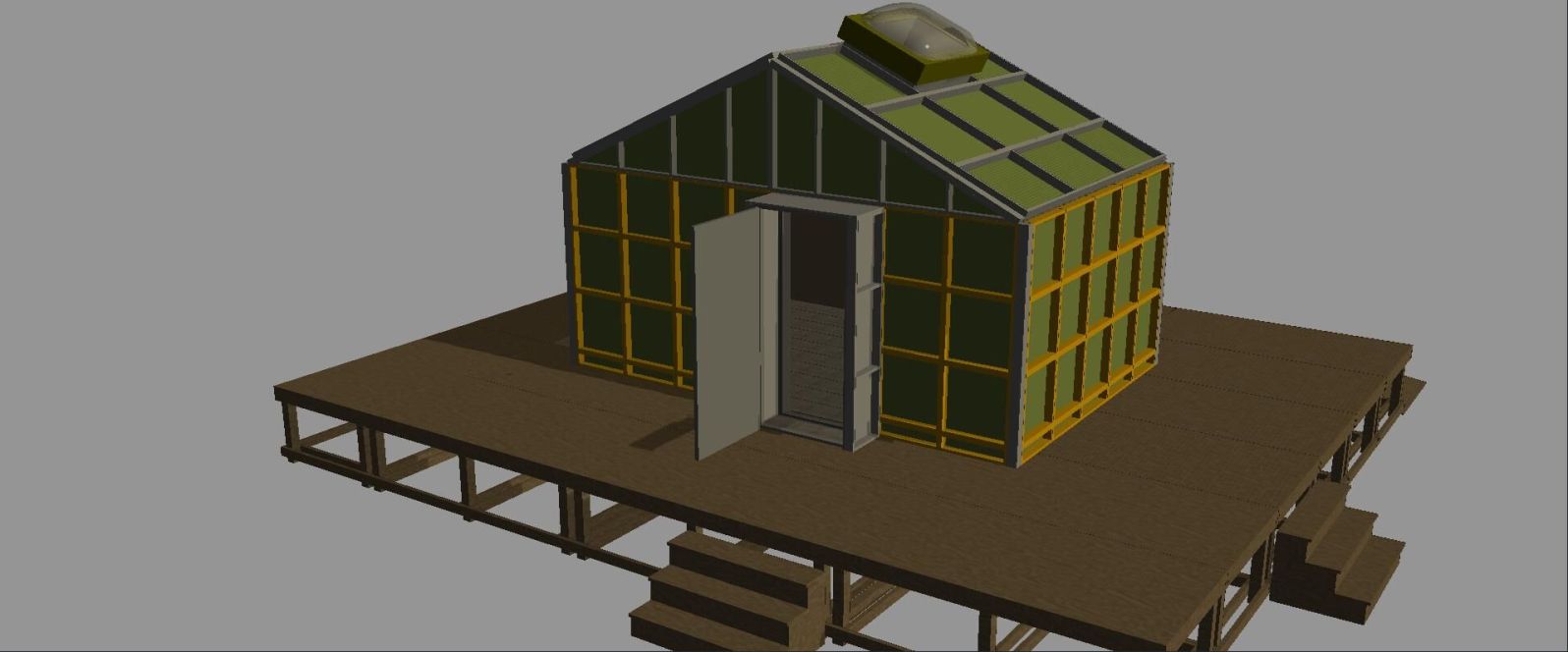

Exterior shed Sketchup plan rendering

ROSE: I really loved the cork and sound panels as it solved the problem, how does no one hear them?

ETHAN TOBMAN: We had a really breakthrough idea a couple weeks into pre-production where my decorator and I, Mary Kirkland, we’ve worked together before and we really work terrifically as a team. We like to approach things abstractly before getting mired in the details of execution. So for example, before Mary even started I approached the idea of captivity as an abstract concept. That led me to, you can start with research of photojournalism from everything from the Fritzl case in Austria to the Castro house in Ohio but it led me eventually to websites like smallapartments.com [site no longer exists] and photo studies of the smallest apartments on earth in Tokyo and Hong Kong and the mud huts of Kenya and the favelas of Rio and that led me to solitary confinement in the American penal system and the cells of the Auschwitz holocaust. As a result, every one of those photos provides you with little nuggets of truth as to how walls would be aged and trafficked. What objects people would keep versus what they would throw out. What they would use to help get them through the ordeal and what they wouldn’t. From there we thought, okay, who is old Nick? Who is this guy we learn almost nothing about. In the book he’s described as just another ordinary monster. We realised he’s in his mid-forties now, mid-thirties when the set was built, it’s probably 2006, he’s in Ohio and he makes around $25,000 a year. He has a flip phone, maybe he has an AOL account and he’s got about $2000 that he’s saved for maybe 4 years to build this, so what does he do? Well he probably goes to a stereo store and says I’m in a heavy metal band, I want to build a sound-proof music studio How do I do it and cork and acoustic tile are the cheapest things he might have been able to use and the easiest things he could have installed on his own so I think when you’re choosing materials, I always think about who the person is who’s buying the material and that dictates to you a lot of the details you employ after that.

Research for Room: aerial views of tiny apartments in Hong Kong

ROSE: I agree. That makes a lot of sense now given his income level. When we see his house… I can’t remember as it’s been 2 months since I’ve seen the film but we go into the house only a little bit or, no?

ETHAN TOBMAN: We do, and I think the reason you may not remember that interior… if I were to tell you that was the interior I found the most important to get right, believe it or not, you’re in there for 20 seconds but what I desperately wanted was for it to not be memorable. I wanted to give you no clues as to who this man was. This isn’t his story. He is absolutely irrelevant to both their captivity and their survival. We’ve seen that movie before. So as a result I wanted his home to be entirely inherited from someone else’s choices. Whatever wallpaper or paint is on the walls is something that exists prior to his occupancy and whatever furniture is there I desperately wanted to make it feel just as random and clueless as those provided to you in a prison.

ROSE: I just remember the door, I really just remember the door and then I don’t remember much more of the space.

ETHAN TOBMAN: There’s a treadmill with a stack of newspapers on it implying that the guy doesn’t work out. So why is there a treadmill there? And the answer is, I don’t know. (laughs) I don’t know anything about him. I can’t glean any information about this man. He has a brown leather couch that could be in a child’s dorm room or in a senior citizen’s home. He has wall to wall carpeting where there are a couple stains but it doesn’t imply that he’s dirty it just implies that he’s lazy.

ROSE: And you guys shot that on location in the Beaches [a neighbourhood in Toronto]?

ETHAN TOBMAN: The exterior was on location. We built the shed and we decorated and painted the interior. We built parts of the house and specifically built Ma’s bedroom on the stage next to ‘room’ and we built the hospital bathroom and parts of the hospital room.

Room being built on a sound stage at Pinewood in Toronto, Canada

ROSE: I was wondering if you could just speak to the colour palette of the film. I loved the affect of the soft pastels in ‘room’ which felt unexpectedly sweet and encouraging.

ETHAN TOBMAN: From the beginning, what attracted me to this project and what I proposed to Len was that we approach Room counter-intuitively and make Jack’s captivity a place that is warm, layered, deeply personal and safe, and to make the outside cold, monotonous, impersonal and frightening. In Room, all Jack has ever known, every object is his friend. Wall sockets and spoons are his family. We worked hard to create a tapestry of history with every color of cork tile, studying which ones were exposed to sunlight, humidity and heat and how his scratches advanced from wear and tear at floor at toddler height, to more sophisticated etchings higher up by age 5. Conversely, this is Ma’s prison cell, so it’s just rough enough around the edges with hints of her struggle to counter the freedom she’s created for him. Outside of ‘room’, we introduced new colors, new textures, materials Jack never would have encountered- shiny white floors, mottled glass, mirrors, thermostats. Every object was a source of discovery and initial discomfort. Playing off the novel, we played with the idea that being liberated was initially a form of imprisonment.

ROSE: The hospital room was a sterile white if I remember correctly?

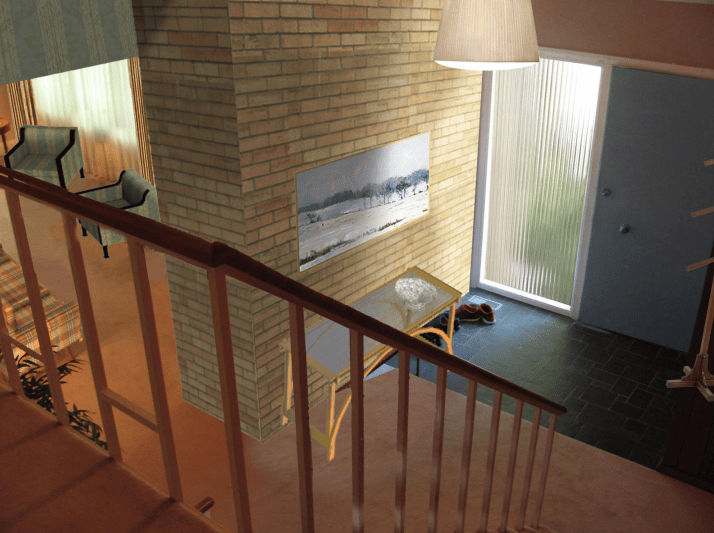

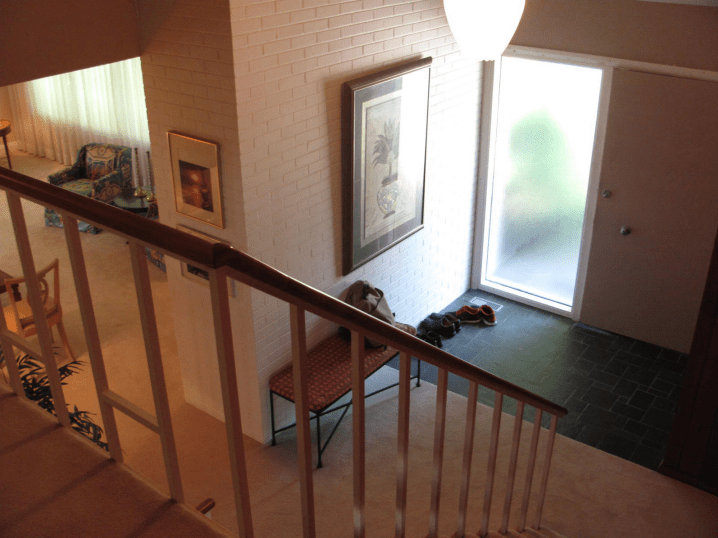

ETHAN TOBMAN: Precisely. The hospital room is essentially just a white limbo box, not unlike the box in 2001. There’s nothing personal about it and to a child like Jack it would feel extraordinarily unsafe. And the house- we chose a Danish modern house because it’s really a series of boxes within boxes so that it feels like you’re still in some form of prison. We used the idea that Bill Macy’s character had moved out and that they’re divorced as an opportunity to explore it’s starkness. This is literally a house that has been fractured and broken in two. We built the bedroom with very subtle symmetry to ‘room’. For example there’s an armoir that has louvered doors much the way ‘wardrobe’ does. We have a collage on the wall that’s not unlike the collage mom makes in ‘room’. I remember this as a freshman in university where people made their dorm rooms look a little like their bedrooms back home. It’s just something we do and I think when you’re a designer when you can employ really subtle parallels it does both help the performance and filmmaking but it also elicits something very subtle in the audience to realise maybe what the underlying theme of the whole project is.

ROSE: I was just thinking that I remember the danish style railing on the stairwell in the family home that felt like a jail cell.

ETHAN TOBMAN: Right. It is probably the number one reason we chose that location, was the idea of foreground, vertical and horizontal lines. Very linear, very strong geometry will feel both inviting and imprisoning. In ‘room’ almost everything is rounded or amorphous. I mean the room may be a box but every piece of furniture in it has some form of curve in it. And the idea that everything in that house would be so linear and hard is very very frightening to a boy like Jack or even a woman, a young adult like Ma who’s trying to find her footing and keeps feeling boxed in one way or another.

ROSE: I was reading an interview with Brie Larson (Ma) where she mentioned that you guys left her and Jacob (Jack) with everything they needed to create the makeshift toys so they made all of them themselves during the process?

ETHAN TOBMAN: I think it’s a mix. I made an awful lot of the stuff that was in there but what’s more important in the mythology of how we made the film is that Lenny was very wisely interested in creating a quick bond between these two actors and you can’t impose that on an 8 year old and you can’t say- okay, rehearsal’s at 9am, see you then. So what’s one way to do it? Well, he watched me one day and we had been collecting an incredible amount of found objects to make the toys. What would they make toys out of? Everything from twisty ties to newspapers to cans and bottles to macaroni. In collecting and making them he thought, you know why don’t we have Jake and Brie do some art together. It’ll break the ice, they’ll have some fun and it’ll serve a double positive by then having toys in the room that they’ve actually created. So some of them were advanced things like the drawings of Jack on the wall, the mobiles that are hanging that need to be weight balanced- that’s some stuff that I did but a lot of the stuff that represents Jack’s experience in that room was something that he created and as a result it was a phenomenal conduit to making him feel natural and alive in that space.

Jack and Ma create makeshift toys in the film

ROSE: Lastly, a question I ask every designer I speak with, what advice do you have to give to those starting out in production design?

ETHAN TOBMAN: Don’t be afraid to find everything fascinating. Read. Travel. Ask questions. Work as a bartender, work in a third-world country. You never know what life experience will inspire you when recreating humanity. Production designers are curious creatures. We’re also in a migrant workforce- so it’s best not to get attached to things. The beauty of creating something exquisite is also in destroying it a few days later. Take risks- lots of them. They ALWAYS pay off. And listen. People tell you so much.

Room Production Design Featurette with Production Designer Ethan Tobman and Director Lenny Abrahamson

Room is now playing in select cities. Please see it if you can. Cinema as an art form and a storytelling platform is desperately in need of more films like this.

How did you feel about Room and its unique process by production designer Ethan Tobman? I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

[…] https://artdepartmental.com/2015/12/19/interview-production-designer-ethan-tobman-discusses-his-work-… […]