Last year, I fell in love with Rocketman‘s production design, so I was very happy to have the opportunity to speak with Production Designer Marcus Rowland recently about his astounding work on not only Rocketman but also his upcoming film, Last Night in Soho. Marcus has been nominated twice for his work as Production Designer on both Rocketman and The Kid Who Would Be King at this year’s British Film Designers Guild Awards.

“I have a bit more of an instinctive approach to design rather than a prescriptive one.”

While awards season has been in full swing for Rocketman, which has been nominated for several awards, Marcus has completed designing Last Night in Soho with his long-time collaborator Edgar Wright. He is now hard at work on the latest adaptation of Little Shop of Horrors. I was lucky to have the lengthy conversation below with Rowland during this very busy period in his career.

Marcus and I discuss his production design process at great length and reminisce about the various trials and tribulations art department‘s must go through to see a project through schedule issues, crew shortages, and lack of studio space. Somehow it all gets done because of skilled individuals like Marcus Rowland and his entire team.

Production Designer Marcus Rowland Talks @RocketmanMovie and @EdgarWright's New Film @LastNightinSoho Share on X

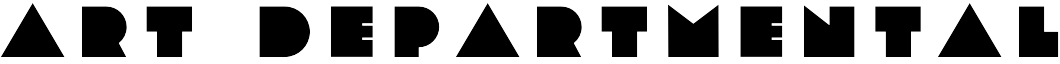

Production Designer, Marcus Rowland, photographed by Last Night in Soho Director, Edgar Wright

Interview with Production Designer Marcus Rowland on Rocketman and Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho

How did you get started in the art department and decide that you wanted to be a production designer?

I went to art school and did a degree in illustration. I actually never switched into film until I was exposed to it after I finished my degree. It was a little bit of luck really.

I was just down in London after finishing college and doing some casual work, and things with illustration, and I bumped into a group of people who were shooting music videos at the time and they wondered if I wanted to help out. I went along with it and at some point, I realized this was something I wanted to do– that it was the perfect thing for me to do.

I’ve always been into drawing and design, and things like that, but I was also partly in the process of leaving college. I was trying to make a living and survive in London which was ridiculously expensive even then. I used to do building work in school and I suddenly realized I like making things so it all seemed like the perfect fit at the time.

It’s just one of those things that I sort of found out of the blue really. Probably not your most conventional way of finding yourself or finding a direction that you sort of followed since then. It’s basically all I’ve done since I was about 22 years old in one shape or form.

The Comic Strip Presents… and Bugs | Production Designer: Marcus Rowland

So you started in music videos in the beginning?

Yeah, well I started on a few and then I got into TV comedy which was quite off the wall stuff in the UK. That’s probably how I got on MVP and that type of stuff. Glam Metal Detectives was a comedy and there was a whole series of other ones before that I did for quite a few years and they were always- well they ranged from sort of alright budgets to absolutely nothing.

You got a good grounding in running around in a truck doing props, making stuff, doing the graphics- basically doing it all and it was a lot harder then because you didn’t have computers at your disposal to do graphics. That sort of got me into it.

Bugs is a TV drama series I did, but all the time I was doing a few promo videos and pop videos. Then from there, I found I really didn’t like the TV approach where you get the script at the last minute, so I decided that I would do commercials for a long time and travelled all around the world doing commercials.

Is that how you met Edgar Wright? How did you end up meeting him?

Well also through a friend of mine, Nira Park, who is Edgar’s producer. She also worked on the comic strip stuff. She was younger than me– she was about 18 and I was 22, or something like that so I’ve known her for a long time. So I was doing other stuff with Nira for a period of time and I sort of arrived through Nira and did commercials with Edgar and got on that way.

You know, with all these things- you knock on enough doors and if you’re persistent someone will open it, but you do need a bit of luck meeting the right people at the right time and getting on with them.

Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010) | Production Designer: Marcus Rowland

You’ve been on quite a whirlwind with Edgar Wright. Scott Pilgrim is one that particularly sticks out for me since I’m based in Toronto and I remember vividly when that was shooting here in town.

It was fun. It’s a shame it didn’t make more money, but it was very good fun. It was great exploring Toronto and trying to stay as true to the comic books as we could. Also staying as true to Toronto as we could, while also having fun with it, rather than trying to completely change it somewhere else. We had a great time.

With Edgar, while he became more and more prolific, I continued to do commercials and work with others because it does take a lot of time with production, editing, publicity and distribution. It can take quite a long time to get each project off the ground.

So I started doing stuff with Joe Cornish, which I did Attack the Block and The Kid Who Would Be King with him.

Oh, I didn’t realize that was the same director on both of those projects.

Yes, it’s all a very small family to be honest, in general. Joe’s a friend of Edgar’s. It’s a bit nice as a way to work. The good thing about that is it makes the language and communication a lot simpler when you have a framework.

The downside of it is you tend to start to do the work earlier– which is great as well, but you’re involved in it a lot more which I do like as much as anything else really. You’re just involved in much more of it than the art department side of it or the design side of it. A bit more of everything.

Attack the Block (2011) and The Kid Who Would Be King (2019) | Production Designer: Marcus Rowland

Did you know Dexter Fletcher previously? How did you get involved on Rocketman?

I had been doing some commercials away and then I just got a call. I was in a position to do it and they wanted me to have a meeting with Dexter and he’s a fantastic, gregarious guy and we talked about it.

In the process of going for interviews I get together as much reference as I can to get a sense of it because it makes the conversations a lot easier if you can talk about, and reference, you know– the way I see it. As much as anything I try to use those sorts of things to find out what they want as well. It’s more of a question of trying to figure out how it all fits together.

It really came from nowhere. I literally went for the interview on Friday and I started on the Monday. It could have been bad but in many ways it was good because I was just thrown in there and you just have to make it work.

Dexter’s a nice guy and a very good director to work for and he’s happy to have input and leave you to do your job. Honestly, and that allows you to put it altogether and discuss what you’re doing. It’s what made it all doable at the time. We ended up building so much more than was originally thought because we could move quite quickly. We would just rubber stamp it and just move on. If it had gone through some of the other approval complexities of the process you need that extra time.

Dexter’s a different sort of director. He can arrive on set and he can make it work. He’s not requiring everything sorted. We did a lot of storyboard too though.

How much lead time did you have with such a short on-board period?

I can’t even remember. It was probably like- it wasn’t that much, it might have been 10 weeks. May have been 12 weeks. Probably 12.

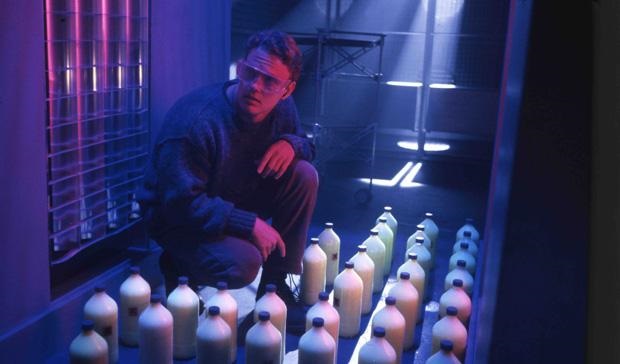

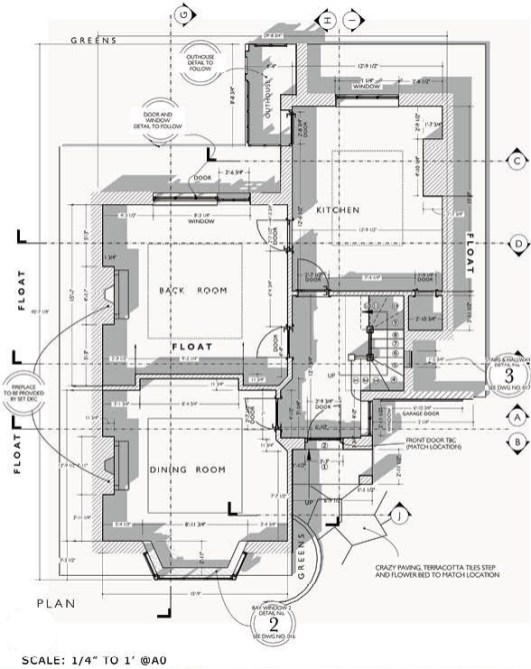

Int. & Ext. Troubadour Club

I read that you guys built 80% of the sets on Rocketman. Is that correct?

I think so. Initially they had some idea as to where we were going to shoot stuff– some of them good, some of them bad. So we recce’d (scouted) a bit more and we were finding it really difficult because there were quite a lot of locations. It would never make a full day on the schedule. To keep up with that volume of unit moves we’d have to lose 2 hours in a day.

Eventually the practicality of the whole situation and the fact that we couldn’t find what we wanted led to more builds. To be honest, the locations were costing almost as much, or more by the end of it, so the costs became more and more expensive so we pulled back bits. It wasn’t like it was a deliberate decision, but every time we gave up trying to find something we’d realize we have to build it and we’d quickly work on some drawings for it.

We were based out of a smaller studio outside London so the biggest crunch point for us was that we only had 2 stages there. The original intention was that we’d build Reggie’s house, the Troubadour, and a few small bits but as it transcribed there was never enough space there.

We ended up looking for a location area, a warehouse space, and fortunately we found a really good one which was a long thin one, with 2 sections open, and literally, we just started lining up the sets all the way down the warehouse and building them as fast as we could. It was quite fun having everything there where you could walk from one set to the next.

The downside of that, of not having the sets in separate stages, is that you have to finish all of them early on before everyone arrives and starts shooting. There were some challenges there but it was one of those things that you work through.

I really enjoyed working with everyone. Dexter’s great. George Richmond, the DOP (Director of Photography), was great. Julian Day, the Costume Designer was fantastic. It does make a lot of difference when you’ve got a bunch of people that, even if you’re not familiar with each other, we’re very much in tune so it was quite an easy process.

Ext. Reggie’s Childhood Neighbourhood

Had you worked with your art department team before, or were you starting from scratch?

I was sort of starting from scratch. There were a couple of people I had worked with before but I was basically starting from scratch. The construction guys I know well.

The last few films I’d done before that were in America with The Kid Who Would Be King, Baby Driver, and Ant-Man. With such an extended period of time you tend to lose quite a lot of crew doing that. It’s very busy over here, so it’s difficult to be consistent with the team really. Ideally you pepper the crew with a few people you know and trust and then you get some new people. The reality is that I generally find that most people who work in the art department have a similar sensibility wherever they are. It attracts the same type of people. I never find it that daunting.

It is very hard to find crew here and you do spend an awful lot of time ringing around and filling particular positions so it can eat up a lot of time just getting people who are available. I know it’s the same way in Canada.

Yes, we always have problems during busy seasons finding the best crew available. You can always find people eventually, but it does eat up a lot of time unfortunately.

I didn’t realize London was similar in that way because you guys have such a large film community and such skilled crews.

Yes, it’s cheap here so now the biggest problem nowadays is just crewing and finding studio space to actually build anything and I think it’s almost gotten worse at the moment.

We have the same problems here with studios too. There is never enough space.

Yeah, I know, because my supervising art director on Scott Pilgrim is a very close friend of mine. He came to do Ant-Man with me and he came to do Baby Driver with me too.

Oh Nigel Churcher, right?

Yes, Nigel, and we had Walter Gasparovic as well as the 1st AD on Baby Driver so we’ve sort of kept quite a link to Toronto after filming there because we met some good people.

Baby Driver (2017) | Production Designer: Marcus Rowland

Nigel’s done so well after all of that and with The Shape of Water and now he’s just started designing which is great.

Yeah, he’s never really rushed into design because he enjoys other stuff too. He’s a bit of a free spirit really. He works with Paul Austerberry as well.

That’s the great thing. I didn’t know Nigel until I went to Toronto. You know, it’s always this brilliant thing that you suddenly meet these people that you have shared interests with and you can build these great friendships. One of the best things about the film industry is the fact that it’s very diverse and unpredictable and with the commercials I’ve worked in so many different countries and it’s a great experience.

It’s become more of a travelling circus where you’re going wherever they tell you to go. I find it interesting that we get to build our crews all over get to know who is great at what they do in various cities wherever you might go.

Yeah, because you’re only able to ship a few people you’re familiar with, but that’s really all you need. That’s why Nigel was brilliant for me on Ant-Man– I know we left that show, but we had a good time and then on Baby Driver. As long as you have a fairly strong central unit you can afford to take risks with other parts of the crew and rebuild each time.

You know, Atlanta’s not exactly filled with hundreds… it’s improved quite a lot, but you know it’s a fairly new industry for them over there. I know a lot of people come from LA to Atlanta usually but you can’t ship everyone from LA. You do have to go with a local crew and you have to run with it.

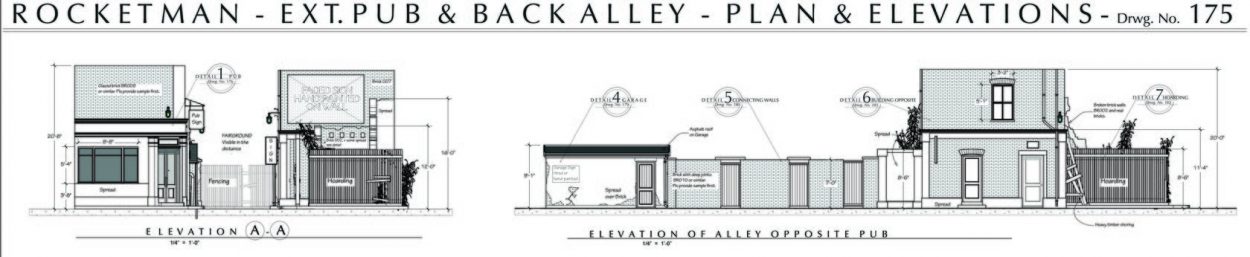

Ext. Pub & Back Alley

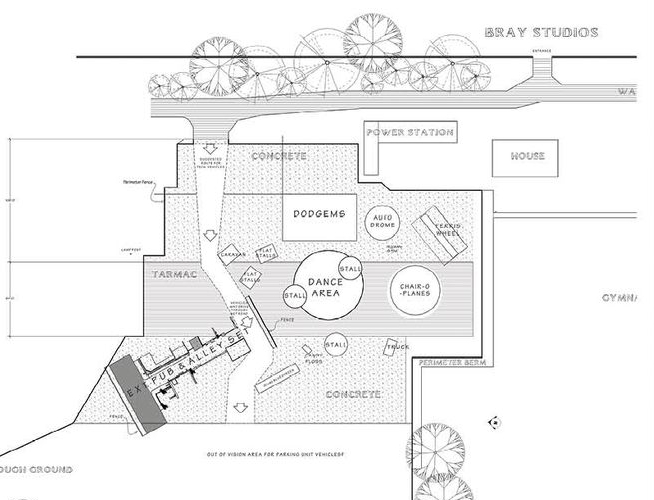

So you had a warehouse and two stages within a studio. So with the scene where Elton is aging and goes to the bar and then to the amusement park and into a different bar– where was that filmed?

That was in the back lot. They called it the back lot but it was basically the carpark outside the studio and so was the Troubadour which was a build just outside the construction shop. Literally everything was squeezed in.

It was 30 feet outside the construction entrance, which we put there because it gave you a nice bit of light and we could warm up the set with the sun. It was extremely helpful when we were trying to make something feel like LA. The sun can make an awful lot of difference, especially late in the afternoon when it starts to feel somewhere in the same ballpark. It doesn’t feel so grey and British and that’s all you’re trying to do.

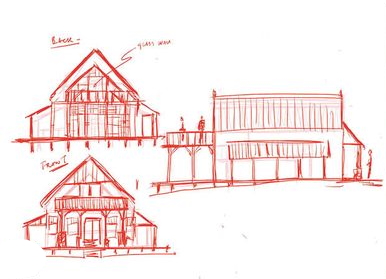

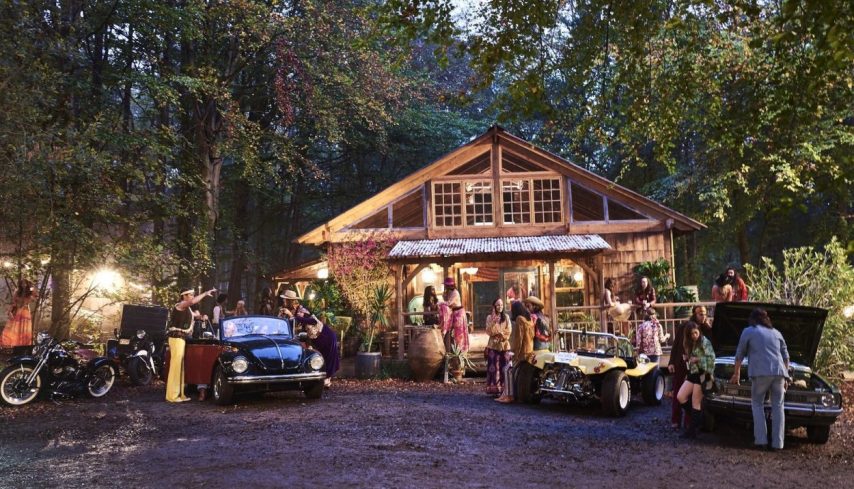

There was the Laurel Canyon Mama Cass house we built in the woods on a farm. It vastly helped by being at night because it gave us a bit of a chance to make it less obviously British with trees and everything like that. Plus we had a bit of digital help in the beginning of that scene. We built that whole house from scratch on a piece of scrubbed ground which was really fun.

Ext. Mama Cass’ House in Laurel Canyon

So you had about 3 months prep and you had to get the majority of your warehouse studio space built before they shot. You’re building there, you’re building Reggie’s home on the studio stage, building loads more on the back lot, and building an entire house in the woods.

So… I suppose I’m just wondering how you guys were able to stagger the builds and the schedule to make it all work. This seems like it would be incredibly difficult, no?

To be honest, it was very difficult. Very difficult. It’s the same as the film I just finished. It’s always difficult, and as much as you try and… I mean, the idea is that ideally, in the schedule, you would hope that the pressure of the whole process is spread across the whole film, but the reality is that the art department’s requirements are so low on the list that by the time everybody else’s requirements are taken into consideration, particularly the actors and their preferences, you’re pretty low down on the priority list.

It comes in massive waves, like a massive panic to get everything drawn as fast as you can, and then you move on quickly to get it built. Eventually, it quiets down, and then it becomes easier again. I’ve never worked on anything that was consistently level. It’s a constant thing- it’s incredibly busy, and then it will ease off a bit.

Certainly, on Rocketman, it became a lot easier because once you got everything built, you’d still have to mettle around with them, but with every set you’d get built, there was one less thing on your list. From every day that you’d start shooting, it would get easier, basically.

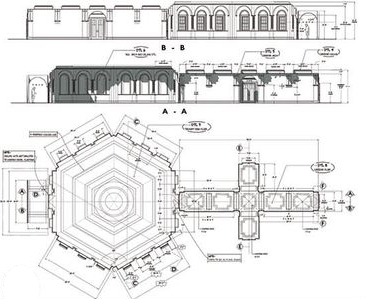

On the film I just finished with Edgar Wright, Last Night in Soho, the intention was that there was a chunk of it on location, based in Soho, and then there would be a whole studio portion of it. Originally, the studio portion was at the end, and the location was at the beginning, but then, at some point between casting and script changes, they flipped it the other way around.

They had to get permission from Central London for the location so we were in a massive panic to build everything and it puts an awful lot of pressure on the construction team, but you get through it and you have to use a bit more overtime up than expected. Then when that’s done it quiets down a bit except that one never got quiet until the end.

The bigger builds became– even though they were challenging in terms of the size and the time we had to build them– you’d know where they are in the studio because we had the space. You could tinker with the amount of work that needed doing.

You could simplify things, but even when you can call in as much labour as possible, it’s difficult because construction labour is really hard to find in the UK, so everyone is trying to steal labour off of each other’s films– off of any film that goes down or gets pushed. Everyone was straight away on the phone hiring them, and we were a barely medium-sized film. The guys who really want to make money want to go on Star Wars or Bond, or something like that, where you can get a full year’s work doing construction so it is a bit of a juggle to try and make it work.

In many ways, though, apart from that, they were the easier bits. The smaller builds are harder because you’re trying to find space to try and squeeze them in. Then the locations, for what they are, are difficult sometimes because you don’t get the amount of prep time that you would want.

In Last Night in Soho, we built some sections of 60s Soho, and so we closed down a couple of streets and did that, but you have so little time to do it, so it has to be a well-oiled machine. Also, it’s a very, very busy place. I don’t know if you’ve ever been there, but it’s wild. So you’re dealing with that logistically and trying to design your way around that with some people not wanting to play ball with the process with shots in restaurants and things like that. So they all have their individual challenges. It’s going to be a good film though, I hope.

Last Night in Soho to be released in September, 2020

With Edgar Wright’s track record I’m sure it will be great.

It certainly looked good. It’s also something completely different again.

With Rocketman, did you have anything happen like that with a location? Given how much of it was built?

Funny enough that’s what made it easier in a way. Once we decided to build, we just had to knuckle down and design and draw each set as quickly as possible but once we did that, it was easier. It is easier.

I mean, I like locations and it’s really interesting to go look at places and certain things you could never achieve in the studio, but if it’s at all possible to achieve it in the studio, it’s a lot easier. I know it seems like it’s more for the art department but it gives you the space and the ability to reinvent stuff and not be tethered to what’s practically possible and what’s already there.

You can just sort of reinvent it and it’s what we did with all of those sort of interiors, like the inside of the Troubadour. We looked at reference of what it looked like, and it was a fairly ugly and messy place. So we just did a more simplified and sympathetic sort of rendition of it rather than a complete pastiche. We just took the bits that were nice really. I only ever really wanted to get the same flavour of what the real place was.

It’s surprising, even things that you think that people would… I mean, on Last Night in Soho we built a whole club, a club that’s been in London since pre-war, since the 30s. So I modelled it slightly on the real thing, but made it bigger and more interesting. Everybody walked in who had ever been to that club and said, oh it feels like the same place but there was not a lot of similarity, you know. It’s amazing how people’s perceptions of memories are that different I think. When you get close enough to the bigger pieces it sort of becomes it really.

Int. Mama Cass’ House in Laurel Canyon

In terms of the design process, how far did you stray from what you came in with on the interview? Did you guys run with a lot of your initial references or was there a lot more finessing of the broad concepts?

It never stopped. That’s the whole thing for me, it never stops. In a strange way, it’s not a piece of architecture. It only really exists on film and so how it’s shot is so important. If I can meddle with it at that point before it’s shot, I will, because it’s about what we see on screen. You’re constantly adjusting things to make it work so it doesn’t really ever stop.

I will constantly change stuff during the design process because as you’re building it, it looks different than the… and the colours might not quite be working. It’s not something that I would sign off on and then walk away from. I like the process of letting it sort of organically evolve. I don’t really like to commit to too much in the way of colours until I see some of the props and what we got.

I have a bit more of an instinctive approach to design rather than a prescriptive one, but the process for me starts with reference. I do continue to build up enough of a back catalogue of things I can refer to as things change, as you know, often things do, when another set comes in, and something else changes. When I go into my back catalogue and go, okay, this makes sense, I’ve got this and I’m not— it doesn’t throw you off balance because you’ve already got the foundation of material that you can use and turn to at any particular part of the film.

It’s also a really enjoyable bit, digging into something like, well, I mean Elton, he’s got an interesting history behind him and so digging into his world and what was around in the 60s and the early 70s and what he was up to was fun. It gives you a great deal of inspiration and hopefully, it gives a bit more depth to the film.

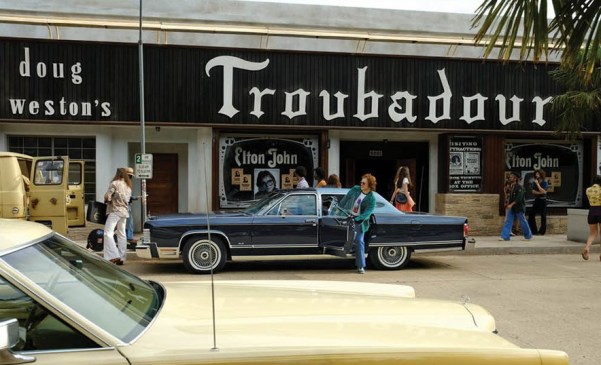

So I design from the references to the rough sketches, to SketchUp and 3D Max — whatever gets us into it. I particularly like SketchUp because I feel that it’s a lot more organic than some of the other programs, but you know we don’t always take it into layout. We often take it into Vectorworks and work on it there and we still build card models. They are still the best way to communicate what the set is going to look like to everybody else.

Ideally the concern is that you’ve gone completely in the wrong direction ahead of time and the team can get a sense of the proportion. We can talk about it and you’re trying to use a combination of both, particularly the contemporary digital approach to the design angle and through traditional methods. They all have their place. It just depends on who is available to design and who’s available to produce these things.

I do think that one of the most important things for me is the card models, just because they’re there in the office at scale and you just leave them around and everyone can come and collect them. From there it sort of brings everyone into the art department and construction world. Sketchup models are great but you have to actively show people around them. Whereas with something like a white-card model you can just leave it and they can peruse it at their own leisure really.

Int. Mr Freedom Shop

And then there are the other parts of the design process when the Set Decorator gets involved. It’s often what they can find that brings another layer to the whole set. I mean, certainly on Rocketman a lot of the detailing plays a big part in Reggie’s house where you’ve got… it’s not a huge set so you’re very aware and very conscious of all of the patterns behind him all the time including the wallpaper.

That’s another decision process that you can’t really make until you’ve got all those design elements together. We used as much as possible, real wallpaper from the era to take us in the right direction. You would find things were much more accidental and less planned, and that was great.

There was only so much authentic era fabric and wallpaper around so in the end it was all about juggling to make it fit. It all becomes a bit of drama tracking down the last roll of wallpaper of that pattern in the world. You just get some really interesting stuff this way.

We could have designed the wallpaper ourselves but I particularly feel that even though it can be done, I don’t always think it’s the best thing. It’s nice to be able to run with some real things.

Int. Reggie’s House

I agree. I do think it lends an aura of authenticity that is very hard to get otherwise. There is something about the texture to it that can rarely be matched. You can feel it.

Yes, absolutely. You can, you can completely feel it. It’s the colours and everything about it. The people that have to hang the wallpaper complain about it everyday applying 50s and 60s wallpaper, but once you get over their moaning, it’s fine [he laughs].

That was the really lovely thing with Reggie’s childhood home- there was a really nice balance between the pattern and the texture and the colour scheme. Sometimes when you go into those desaturated earth tones in a big, bold film, it can end up makng a set look flat or bland, but it didn’t do that in this case.

Yeah, I know what you’re saying. Sometimes it just flattens it all out. The textures in the floor surfaces and the wood against the linoleum which was whiter, worked. Plus the stained glass really helped. It’s just one of those things… on that one we had a little bit of time to get the basics up, find the right wallpaper, put some up, see what that looks like, and tweak it like a house really which was sort of a luxury.

If something isn’t working, add something else. It’s not an exact science. It really isn’t… you can predict a certain amount of things. You can predict the shape you want it to be, the sightlines you need in the set, and you can work out that it’s going to be difficult to shoot in. So you can figure out how to break the set up into pieces and what the angles would be– you can sort of work that out, but I don’t think you can work out the whole look of it until you’ve got the pieces there.

I didn’t do any visuals for that particular set. Obviously, the bigger ones we did some. We had a very good concept artist working from the SketchUp model of the rendering and then working on top of it and that was a really good way to play around with the bigger sets to get everyone familiar with it.

On the smaller ones though I didn’t ever have enough information to test textures in renderings. It always just happened. You sometimes don’t want to do too many visuals of things that you want to have the freedom to deviate from anyhow. You can be surprised by the result. We did spend a lot of time playing with it, with the materials, set dec, props, whatever we could find. It was all a piece by piece process.

Int. Ray Williams’ Office

Did you know from the beginning that you were going to run with the earth tones for Reggie’s early years and then go into the bolder colours? Was the colour scheme an organic process?

Yes, I think it was organic and it was a pretty natural decision. We definitely felt it was the right thing- since it’s a world he’s reflecting back on which was not a world of complete joy. Plus 50s Britain was a very mundane and dour place after the war, you know, until the 60s came.

After the Victorians and the end of the Edwardian era, everything grew slightly down really. That doesn’t mean it was completely devoid, but it definitely wasn’t a vibrant, expansive, or optimistic world as it became later on. I mean, because Elton’s telling it, it frees you up to be more imaginative, but I always imagined it in that tone.

I sort of… when Julian was doing the costume, it was always great to have the focus on Elton in the therapy room and marching down the street. You want to be drawn in by Elton, because it’s his tale. He needs to stand out in the environment and that sets the playbox for the film really.

And was that a build as well– the hallway that leads to the therapy room?

Yeah, that whole hallway and room was built.

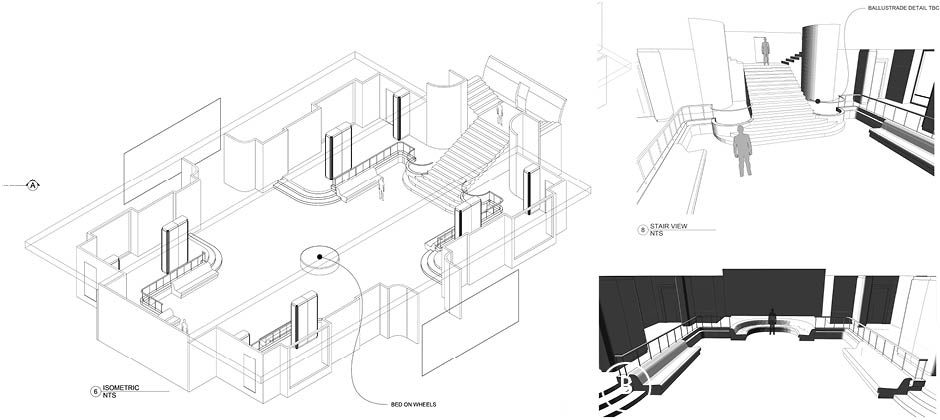

Int. Hallway & Group Therapy Room

There were so many details in that set that just really worked, like the arches that essentially point to Taron Egerton as Elton John in the center which lead your eye in to who the story is really about and what he’s going through.

Yeah, and that was always the intention. With that, we always knew that was quite a difficult set. Once you find it, it feels like any other set, but at the time it was difficult to find where you’re taking it, because it could have easily been, you know, the real world of a clinic which could be a very dull, mundane, 60s building, more hospital-like and it would be very dour.

Eventually we looked at a few locations and we couldn’t really find the right location so we were designing the interior before we had the exterior, but it was a decision based from looking at some other spaces. It was a combination where I stole bits from different places to create one world. I didn’t really see it until we started doing it.

Once it became a bit grander, at a bigger scale that hints at it being more of a retreat it became a bit more like a priority which started to make sense for me. Just by tone and by pairing it right down so there’s not a lot in that space apart from the architectural detail at the pinnacle of it.

That was the bit which made it more admissible and made it more, I suppose, more pointed. It had the reference to a therapy group or medical room, just by keeping it as simple as possible, but, yeah, it would have been a very boring set had we not been able to incorporate the architectural features into that space.

I loved when he was in the hallway making his way to the room, because that’s when I thought, you had to have built that because it’s just too perfect in the way that you’re able to move in such a precise way that actually works.

Well, thanks. That’s sort of the way it works. If you want it to work, or you want it to fit, you can make it work in location but you have to flex. If you can build it, you can run with it, and make it much more precise.

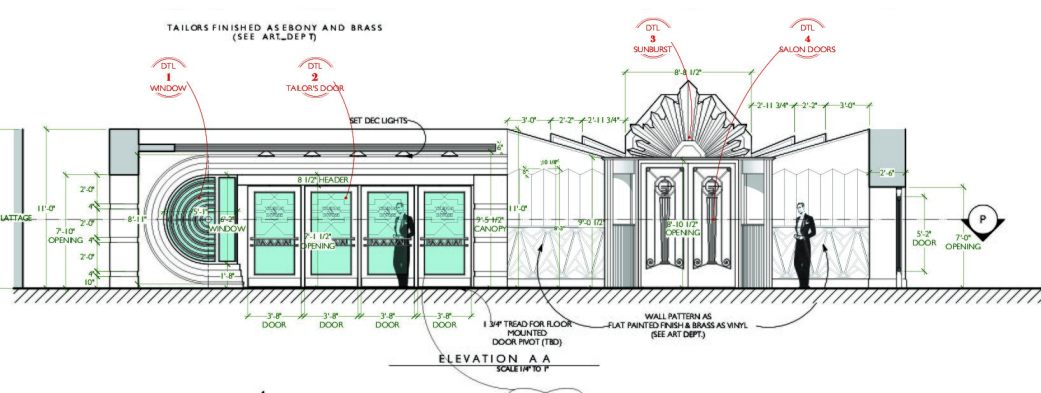

Int. Art Deco Salon

Now with the musical numbers, did you have a harder time sorting out how that was going to work, because a lot of times , so much rehearsal time is needed and they’re sorting out what they need as they go but you have to be designing and building often before they figure that out. Was that difficult?

Yes, basically that’s it. Yes, because we were designing and building without input from them at certain points then they come along and we have to rationalise what they want and need.

The songs existed, sung by Elton, but obviously Taron’s reperforming them, they’re retiming them, they’re cutting them to fit a particular piece of time, and sometimes that changed, and we built bits of set that I feel I would have preferred slightly smaller because we gave them a lot of dance space and I’m not sure they always filled it, but you have to sort of find your way.

The only thing that I would say most about that, is that throughout that period of time they did quite a lot of good rehearsal which informed how we used the stage which then we could adapt the set so it’s all running concurrently at the same time. We’re checking on them, and sending the drawings down, or even building bits of set that they’re performing on.

The whole dance sequences, there was a lot more shot that didn’t end up in the final film. There were more dance numbers. One on top of a big golden record which I think was in the trailer but never found its way into the actual film. I think it may be on the DVD.

That was a big sequence, and then there were other bits that we shot in that Hollywood sequence which was shot very quickly. I would have liked it better, well… there were moments where they didn’t quite do justice to the set, but other times you win.

The scene when they’re in that other Studio 54 club, that was a big club and there was a lot more of it. There was a plane at the top, which you can only just barely see it.

Int. Plane & Club

Was that a build as well or was that a location?

That was a build as well.

Oh wow. You guys really did a lot of work.

Yeah, I know. It’s got half a plane at the top of the stairs which you barely see now because the initial sequence, you see him and then he bursts out the jet and comes down the stairs and then there’s a whole bigger performance with Jake Shears performing the song and then you can still see it in the background with his headgear on. He did a good job but I think they didn’t want to confuse people since Taron should be singing all of the songs and they re-edited the song in a way to favour Taron’s performance.

As the art department, I would have preferred to have seen it as it was shot, but as a film producer, they have to keep the pace going married with the narrative they’re crafting. If the design no longer fits with the narrative of the film and the overall editing of the film, than it’s all part of the process. But yeah, that was a nice big set. Those were big builds in the warehouse space.

Int. Recording Studio & Performance Stages

There were so many bars, clubs, and stages. Did you guys turnover these sets as much as possible?

If there was ever a time we could reuse a set, we did. Some of the stage sets are the same stage redressed and a lot of the backstage area and then there are some bits that aren’t in the film that we redressed. It was more if we could get away with doing it, we would.

The recording studios were still in there, I think we rebuilt sections and redressed them. It gives you a headstart when you have some of the structure. You can change it, but it’s easier to start with something half standing already. It’s just a much simpler process.

You can’t tell in the movie at all.

Yeah, we tried to reuse what we could. It’s much cheaper to do that too. Eventually I had this warehouse where some sets had to come and go just to get other sets up as well. You run out of space pretty quickly.

There’s never enough space anywhere. It’s sort of driven by the schedule as much as anything else. It’s all possible to do it if you feel it’s not going to compromise anything. Most of the time, I think it would be pretty difficult to spot unless you’ve made it too similar.

Int. Elton John’s Los Angeles Home

How much access did you have to Elton John and his images and files? I read that you guys visited his home?

I mean, yeah, Set Dec and Costume had access. He’s got quite a lot of back catalogue in storage, particularly when it comes to costume and glasses. I think they had access to that. I didn’t go to the warehouse to look at his stuff, but I don’t think a lot of that stuff was there. The stuff that we were sort of interested in was more of the 60s, 70s, and 80s stuff which he sold off. He changed his stuff.

I did get the opportunity to go around his house and that was a great insight into his personality and his love of collecting and detail and things like that so that was really useful and I mean he’s got an incredibly impressive art gallery there, with the most beautiful photographic prints so it was a wondrous thing.

You don’t get many opportunities to wander around Elton John’s house looking at everything so it was a rather great thing working on the film and working on the design, catching these opportunities as they come. It was fascinating to see what he was willing to collect and how it changed.

We tried to reflect that in his London-based house as much as possible. It’s dressed in there, but it’s fairly fleeting, and yeah, just trying to capture some of his personality that was in his original house.

Int. Elton John’s London Home

Was there anything that really surprised you, that changed the way you were going to do something, once you went to Elton’s house and did more in-depth research on him and the way he liked his things?

I think it was just the fact that everything was incredible– everything was laid out… it was surprisingly old-fashioned in certain respects and then very contemporary in others, but literally on every surface that you wandered into his house, I mean, every surface in the main rooms was covered in meticuolously laid out items.

One table would have snuff boxes measured and laid out to perfection, and you couldn’t really get to the surface. The same thing applied to the piano laiden with pictures. There isn’t a spare bit of space you could squeeze in another one and that’s all continued throughout the house. It was a… it’s obvious he’s an ordered but very compulsive person if that’s correct to say.

Int. Art Nouveau Performance Number

What was the most challenging and rewarding set on the film?

That’s a difficult question actually, because it’s a bit like picking a favourite. I think none of them were more challenging than any other. I think, to be honest, it was just so difficult, they all had their issues and you just sold them as they came up. I think in certain terms, obviously, the ones we were building outside were more challenging. I don’t think there was anything that was just right. The challenge was always the logistics of trying to build in one space and trying to get a sense of how it could come together.

Probably the one that took me the most out of my comfort zone is the weird one, the set that is very decorative which has that picture, when Reid sacks the original manager and there’s a pinball machine in there. That’s a room which is a build. I sort of didn’t know where to take it so I went completely over the top, because I never really quite saw… I really, really liked it in the end, but I was never quite sure how that was going to turn out until we had it together.

We manufactured the carpet, and colour tones on the walls and had to decide how much detail to put into it. Trying to do something like that with a particularly involved and decorative finish in a fairly short space of time was hard. So that was probably the most fairly freaky bit of the film for me. Yeah, that whole set and the artwork in general.

I have the painting downstairs in my home but I haven’t put it up because it’s so huge. Designing something that’s going to be featured as a painting, but it wants to look like somebody’s painted it and it’s not being done by somebody that knows it well. You can’t use the styles of anybody else or you’re just going to get to close to it. That moment when it all came together and the painting looked good on the wall was memorable.

That was probably a bit more worrying because I would have hated to see something that I felt was very poor, where you would have questioned why this painting was worth any money and how he could have put it upside down which was a challenge in that space even though it wasn’t the biggest set.

For me, it felt slightly more out of my comfort zone, because you know it’s very easy to design things that are slightly easy and to go down a path of something similar to what you’ve already done after you’ve built up a certain back catalogue. You always need to push and make it a bit different and that’s what you should do for yourself. Try to do something different.

Thanks so much for speaking with me today. I can’t wait to see Last Night in Soho.

Thanks so much. It’s going to be good. It’s going to look good anyway.

Int. John Reid’s Office

What did you think of the production design on Rocketman? Are you looking forward to Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho? As always, we would love to know what you think in the comments below.